The Moomins and the adventures of everyday life

Dana Gaskin Wenig on "Finn Family Moomintroll," our Sustaining Book for November

Each month, writer and children’s book expert Dana Gaskin Wenig chooses an enduring children’s book or new classic to explore in depth. This month she travels to author Tove Jansson’s enchanting world of the Moomins.

Children’s books were—and still are—not just an escape into fantasy, but a way of grounding myself in the world.

In which Moomintroll and his parents find Moominhouse (after the Great Flood) in what they come to call the Valley of the Moomins. And how their round, blue house becomes a refuge for Moomintroll’s friends old and new and affords this delightful collection of beings a sense of safety and security, a base from which to have fabulous adventures.

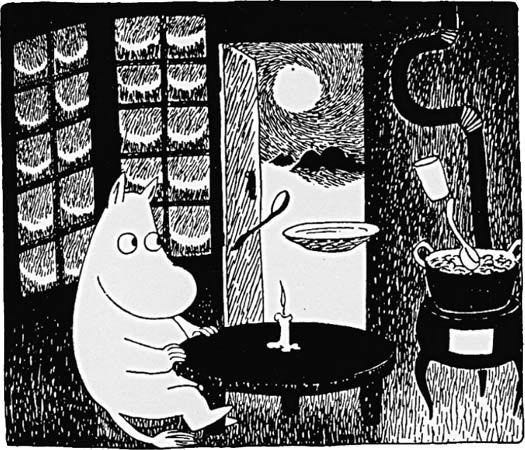

Tove Jansson’s Finn Family Moomintroll (published in Swedish, 1948, and in English, 1961) is a book I dearly wish my parents had read to me, but I didn’t find it until I had my own child. No matter, I fell in love with the stories and enjoyed reading them aloud to my daughter, making sure to share each finely drawn illustration with her as we learned about the ensemble cast of characters that make up Moominland and followed them on their many adventures. I can’t seem to stop reading these books; just last week I read a chapter of it aloud to my mom and stepdad while waiting in a doctor’s office together! They were so charmed.

Tove Jansson both wrote and illustrated the Moomintroll books, of which this is the third of the chapter books, so rather than an illustrator setting their creative intent on expressing an existing manuscript the way John Tenniel did for Lewis Carroll’s The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland and E. H. Shepard did for Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, what we experience in this series is the coordinated creative flow of one person in two different mediums (writing and illustration).

Both Jansson’s parents were famous artists, her father the sculptor Viktor Jansson, and her mother the graphic designer and illustrator Signe Hammarsten. Tove was an accomplished painter and worked from the 1930s through the early 1950s as cartoonist and illustrator for the anti-fascist, satirical magazine Garm. She was also a poet, lyricist, and playwright, and illustrated Swedish-language editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, as well as Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, and an edition of JRR Tolkein’s The Hobbit in the 1960s. Even fans of John Tenniel’s illustrations (or the many other illustrated versions of Alice in Wonderland, will enjoy Jansson’s illustrations for Alice. I think they are gorgeous.

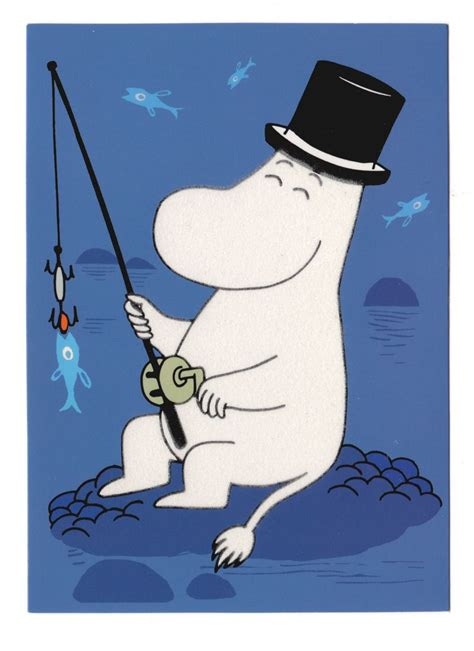

The Moomintroll family is very dear, Moominpappa in a sort of loosely engaged way, preferring to retreat to working on his memoirs, and deferring to Moominmamma on most things. And Moominmamma is magnificent. She is both kind and honest, helpful and encouraging, and she welcomes all comers, but she also pleases herself. A woman after my own heart, Moominmamma carries a large handbag full of “dry socks and sweets and string and tummy-powder and so on.” (I also believe in being prepared for as many eventualities as my purse will manage.)

The descriptive chapter headings are delightful and worth reading (and show up not just in the table of contents, but at the beginning of each chapter.). One of my favorites is “Chapter II: In which Moomintroll suffers an uncomfortable change and takes his revenge on the Ant-Lion, and how Moomintroll and Snufkin go on a secret night expedition.” This is fun, but it also gives younger or more sensitive children enough information to prepare themselves for the possibility that the story may have some twists and turns, but it’s only Chapter II, so things turn out okay. Of course, expeditions mean finding things, and found things are not always benevolent (see the Hobgoblin’s hat, Chapter II, I’ll say no more on that for now).

There are moments of tension, but they are quickly resolved, so this book is great for any age who can tolerate some pages with no pictures. One favorite scene is when Moomintroll’s appearance is mysteriously and drastically changed. When he finally realizes that his friends really don’t know him, he turns to his mother:

“Moominmama looked carefully. She looked into his frightened eyes for a long time, and then she said quietly: “’Yes, you are my Moomintroll.”

And at the same moment he began to change. His ears, eyes and tail began to shrink, and his nose and tummy grew, until at last he was his old self again.

‘It’s all right now, my dear,’ said Moominmama. ‘You see, I shall always know you whatever happens.’”

Being known by the people who love you, even when you are not feeling yourself, is vitally important, and healing.

And friendship is very important in these stories. Snufkin with his flute and his green hat, the animal Sniff with his “sleep-crinkled ears,” and the Snork Maiden with her forelock and her love, are all very dear friends of the Moomintroll, as is the Snork, Hemulen, and The Muskrat (a philosopher). My two favorite characters are Thingumy and Bob who speak a special language. In later stories we meet Little My, Too-Ticky, Mrs. Fillyjonk, and more. In reading about the author, I’ve learned that these characters, perhaps all of them, are based on Tove’s parents, her loved ones, and her close circle of friends.

The stories depict adventures of everyday life: walks, bathing in the sea, waking from a long nap, as well as interactions with strange characters like the Hobgoblin and the Groke, happenings beyond the control of the group, and expeditions with friends and family. Moomin House is a safe base where each creature finds comfort and refuge in things that remain stable, and in a sense of tolerance that exists in the extended Moomin family. It’s not simply tolerance, but a subtle, deliberate celebration and acceptance of the inherent value in the quirky differences of each individual: their mannerisms, ways of communicating, secrets, timing, the incomprehensible ways we each respond to the world as it is. This is the throughline in Jansson’s work, this choice to accept and keep an open heart, even against the backdrop of the times.

Philip Nel, in his Manifesto for Children’s Literature; or, Reading Harold as a Teenager, reminds us that “Children’s books have much to give those of us who are no longer children. There are levels of meaning we may have missed when we read the book as a child. Adults’ experiences may grant us interpretations unavailable to less experienced readers, just as children may arrive at interpretations lost to adults who have forgotten their own childhoods. In children’s books, there is art, wisdom, beauty, melancholy, hope, and insight for readers of all ages.”

I would take it a step further and say that even when we’re not consciously interpreting the meaning of a story (at any age), often we still take it all in. These stories offer example after example of what family life and childhood and parenting could be like: freedom, encouragement, safety and adventure, kindness and firmness, conflict and respect.

In the first books of the series, The Moomins and the Great Flood, Tove “portrays an idyllic world, a utopian bubble withstanding encroaching, life-threatening natural disasters, floods, comets, and volcanic eruptions.” The characters respond to each other with such sensitivity. When the collector Hemulen has completed his stamp collection, he is bereft and tells Moomintroll and the Snork Maiden, “I said you’d never understand me, didn’t I?” The two friends then “waited respectfully for him to unburden his soul.” How many self-help books recommend we do just that rather than jump in with advice and fix-it questions when a friend is struggling?

Moominmamma’s voluminous handbag full of remedies and her example of steady care, and how she chooses to handle the unexpected, influences the whole group. And when the group of friends begins annoying each other (and her), she is happy to send them off on an adventure with too many supplies. Thrilling adventures ensue featuring mysterious signage, a huge, black hat, an annoying Silk Monkey, and a secret cave. And the small animal Sniff serves as Path Pioneer.

In an article by W. Glynn Jones on the website The History of Nordic Women’s Literature, the author suggests the first Moomin book, written during WWII, was intended as an allegory for the second world war, and comments that the early Moomin books represent “the peaceful valley of the Moomintrolls, where maternal norms rule, and the meaninglessness of war is far away.” Finn Family Moomintroll is an antidote to war, an expression of hope for better relations between people and nations.

“And so Moominhouse was rather full—a place where everyone did what they liked and seldom worried about to-morrow.”

Moomintroll characters, comics, illustrated books, and chapter books, are classics translated into 60 languages and are famous the world over, but came late to the United States. A favorite question of mine, when I was a bookseller, was: Do you know about the Moomins? Either the person’s face would light up with wonder or go blank. Even then someone might know of the Moomin television series, the Moomin cartoons, comic books, and illustrated books, but be unfamiliar with the chapter book series.

Ms. Jansson was a Swedish-speaking Finnish author, so the books were written in Swedish originally. Finn Family Moomintroll was the first of this series to be translated into English, but The Moomins and the Great Flood, book number one, wasn’t published in English until 2005. Because of this, English-language readers have not had the opportunity to experience the arc of the series until very recently.

Beyond the many Moomin books, both chapter books, comics, and cartoons, and illustrated books, the characters and their adventures are available as a TV series, a theme park in Finland called Moominworld, the Moomin Museum in Tampere, Finland, and more. The official Moomin Store (online) carries everything from coffee cups to mittens with favorite characters from these stories, but the stories are where the magic is.

For adults and young adults, Netflix released a movie (image below) about Tove’s personal life and her creative works in 2020 which I thoroughly enjoyed. We learn about Tove’s life with her parents, her relationships with both men and women, and how she met the love of her life in 1956, her partner Tuulikki Pietilä, an important American-born Finnish graphic artist born in Seattle, Washington. The character Too-ticky in Moominland Midwinter was based on Pietilä.

Initially the couple lived in separate houses attached to each other by a secret attic passageway. (Homosexuality was illegal in Finland until 1971.) Later they were able to live together and were the first same-sex couple to represent Finland at the Independence Day reception at the Presidential Palace in 1992. Their relationship flourished for forty-five years—they traveled the world together, collaborated on many projects including a five-story Moomin House on exhibit at the Moomin museum in Tampere, and enjoyed summers together in the cabin they built on the island of Klovharu off the coast of Finland, until Tove’s death in 2001. Tove Marika Jansson died when she was 86 years old—she rests in the Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki.

It’s entirely worthwhile to read all of Tove Jansson’s works, her Moomintroll series, her novels for adults, her cartoons, and spend time with her paintings, which are phenomenal.

Dana Gaskin Wenig is a writer, writing teacher, and former bookseller. She lives in the Seattle area.

320 Sycamore Studios is a children’s book publisher. Visit our Bookshelf page to read our stories for free. Books are also available for purchase on Amazon.

This was excellent. I'm a huge fan of Jansson in general, and especially the Moomins, of course. (Too-Ticky is my person.) Thanks, Dana!