12 Ways of Looking at 'Alice in Wonderland'

Dana Gaskin Wenig on the Lewis Carroll classic, our Sustaining Book for August

Each month, writer and children’s book expert Dana Gaskin Wenig chooses an enduring children’s book or new classic to explore in depth. This month, she falls down the rabbit hole and discovers twelve ways Alice in Wonderland continues to reverberate through Western culture a century and a half after its publication.

There are many stories that tell us about life. But rare is the story that shows us what it feels like to be completely alive — always changing and growing in an infinite world that is itself changing and growing.

The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland — written in 1865 by Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson’s pen name) — is one of the rare stories.

Alice is about following your curiosity into adventure, accepting that adventure, and meeting all the confusing, hilarious, and nonsensical creatures and experiences life throws your way with courage, determination, and humor.

Maybe that's why it was my favorite book when I was small. I loved the cranky, quirky creatures, the wordplay, and the little songs and poems. My mother read it aloud to me countless times, along with Through the Looking-Glass (1871). I used to get the two stories confused until I realized that Through the Looking-Glass is based on the game of chess, whereas most of the characters in Alice in Wonderland are “nothing but a pack of cards!”

Alice in Wonderland is one of my favorites still.

Here are a dozen reasons why.

1. It helped invent childhood

“Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it.”

And so it begins.

Alice was written in the Victorian era, a time when childhood is said to have been “invented” — with efforts to end child labor and the introduction of compulsory schooling. In a very literal way, Alice is the narrative of childhood itself — transitional, frustrating, abundant, and delightful. Alice is one of the first that is both for a child and written with insight into a child’s perspective on adulthood. Plus, it’s just fun to read. It’s also one of the first for children from that time that contained illustrations. Indeed, Lewis Carroll hand-lettered and illustrated Alice’s Adventures under Ground — the first version of this book — and presented it to Alice Liddell as a gift. (That version has since been printed in facsimile form.)

2. It shows beauty is worth striving for

Getting to the “loveliest garden you ever saw” becomes the motivation for Alice in the first chapter. But she’s always the wrong size — too big or too small. (Isn’t that what growing up feels like?).

She “longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and cool fountains . . .”

Is Alice following her curiosity again? Is she just drawn to the beauty?

In Victorian times, the popular style for gardens had swung from natural to more orderly gardens filled with massed beds of flowers in exotic colors in intricate designs. “And so it was indeed: she was now only ten inches high, and her face brightened up at the thought that she was now the right size for going through the little door into that lovely garden.” But she didn’t have the little golden key anymore. . . We never see the garden, and Alice almost drowns in a pool of her own tears over her yearning for its ordered beauty, but these glimpses of a lovely garden keep her going.

If you find your own curiosity irresistibly piqued you can visit permanent Alice gardens in the American South (Atlanta, Georgia, and Memphis, Tennessee) as well as at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Sydney, Australia.

3. It inspires great art

Forty years after this book was originally published (it has never been out of print), it entered the public domain in 1907.

In that year alone, eight new editions were released. One was illustrated by Arthur Rackham, the leading illustrator during Britain’s Golden Age of Illustration. But I recommend you start with the original, unabridged version of Alice in Wonderland (and Through the Looking-Glass) with drawings by Sir John Tenniel.

Tenniel was a well-known, English political satirist, but he’s most famous now for the 92 illustrations he did for Alice in Wonderland. We know he was a perfectionist, because when the first 2,000 copies came out and the reproductions of his works were not printed up to his standards, he asked Lewis Carroll to have them destroyed. Carroll was able to get most of them back (he had given them out as gifts), but a few still exist, most in museums. (There are 92 illustrations by Tenniel between The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass.)

Bryan Talbot, British comics artist (also of DC Comics fame), has said, “The Tenniel illustrations and the text of the books work in a similar way to text and illustration work in the comic medium, in that they blend together in the mind of the reader to make a whole, one that’s bigger than the sum of its parts. For example, Carroll never describes the Mad Hatter: our image of him is pure Tenniel.”

Talbot is so right, yet the perfection of Tenniel’s illustrations hasn’t stopped hundreds of artists from illustrating different editions of this book, the most notable being the surrealist Salvador Dali. His version of Alice in Wonderland was published in 1969 and includes illustrations for each of the twelve chapters, and a “four-color etching” for the cover. Only 2,700 were printed, each signed by Dali.

Other artists who set their hand to art for this book are Gennady Kalinovsky, illustrator of the novel The Master and Margarita; the manga artist Okama; Yayoi Kusama (famous for her rooms filled with polka dots), and Tove Jansson (author/illustrator of the Moomintroll series).

The wealth of art this book has inspired is remarkable, and there’s nothing stopping you from having multiple editions of it, but Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations join with Lewis Carroll’s words give us the heart of the story, so that is the edition I love and recommend.

4. It’s a coming-of-age story

At one point, Alice says, “I’d nearly forgotten that I’ve got to grow up again! Let me see — how is it to be managed?” (I’m still asking myself this question.) At another point she remarks, “How puzzling all these changes are. I’m never sure what I’m going to be from one minute to the other.”

The themes of growth and change are the center of the book. For me, Alice in Wonderland is, and always has been, a story about a child who is surprised by growing up, a child who sometimes still feels small. (I think we’re always all the ages we’ve ever been.)

Carroll framed Alice’s time in Wonderland as a dream, but I see it as a coming-of-age story. I identify with the child who follows her curiosity, takes a leap of faith (down the rabbit-hole), and engages with strange, magical creatures who are by turns colorful and amusing, dear and annoying, helpful and difficult, in a world where she doesn’t know the rules. And I still identify with the girl who can talk with animals and plants.

What’s more, I have come to see Alice as a superhero. Like an Incredible, she stretches her head above the treetops, then shrinks to the size of the blue caterpillar who tells her “Keep your temper.” Ashley C. Ford, author of the memoir Somebody’s Daughter and co-host of the HBO podcast “Lovecraft Country Radio” says, “The worst thing that can happen to a superhero … is that they are abandoned and confused with this new power. … “The best thing that could happen … is to have another superhero show up and say, ‘Let me teach you how to fly.’”

The strange denizens Alice encounters in Wonderland don’t teach her “how to fly,” but her interactions with them do teach her how to thrive in the world as she grows and changes in a world that is also shifting and adjusting.

Whether this story represents a dream, nonsense, a shamanic journey, or growing up, Alice’s adventures teach her that she is strong enough to find her way even when she is sad or scared or angry, that she can survive confusion and difficulty, and that she is capable of speaking up to people even when they threaten her. I identify with the girl who shouts “Nonsense,” when the Red Queen threatens to behead her.

5. It’s a pillar of Western civilization

Don’t believe me? Consider …

After 157 years, this Alice has permeated European and American culture and beyond. It’s been analyzed by philosophers, mathematicians, psychoanalysts, and literary scholars researching the book’s allegorical, mathematical, psychoanalytical, political, metaphysical, and Freudian levels, and more.

In 2015, the 150th anniversary of Alice’s publication, there were articles in many major newspapers and magazines, exhibitions in museums, and The Alice in Wonderland Anthology was released with contributions by over 60 artists and writers. It seems the world went down the rabbit-hole on the project.

I’ve also discovered that there is a psychological disorder, discovered in 1955, called Wonderland Syndrome, in which people experience the sensation of “opening out like a telescope” the way Alice does after eating a small cake decorated with currants.

6. It inspired some great music

The Sixties gave us multiple musical hits inspired by Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. John Lennon said that the song “I Am the Walrus” was inspired by “The Walrus and the Carpenter,” a poem in Chapter 4 of Through the Looking-Glass. And he said the creative idea for “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” came from a drawing his son made and the nonsense verse of Lewis Carroll.

Perhaps the most notable Alice-inspired song is “White Rabbit” by Jefferson Airplane. Grace Slick, the lead singer for the band, belts out:

“Go ask Alice When she's ten feet tall And if you go chasing rabbits And you know you're going to fall Tell 'em a hookah-smoking caterpillar Has given you the call Call Alice When she was just small”

Between the 1966 television movie of Alice directed by Jonathan Miller and Grace Slick's White Rabbit, “Alice” is forever fused with 60s rock for generations of us.

Miller’s Alice (there are 27 movie versions as of this posting) features John Gielgud, Peter Sellers, Eric Idle, and Anne-Marie Mallik as Alice. It’s filmed in black-and-white (there was no money for color on the production) and its long, slow shots and odd camera angles combine with a Ravi Shankar score to produce a psychedelic or possibly nightmarish version that I am not sure I like. (The intended audience was not children.)

If, after reading the books, you decide to show your own kids a movie, try the 1999 version with Tina Majorino. It’s not true to the story, but the characters are delightful. I also enjoy the 2010 version directed by Tim Burton.

7. It’s mathematical (and anti-mathematical)

Hanna-Barbera’s movie version of Alice in Wonderland has Alice jumping through the television screen (the way she climbs through the mirror in Through the Looking-Glass) and falling down a rabbit hole lined with transistors and electronic equipment. Countless times I’ve heard friends say they have “gone down the rabbit hole” scrolling their phone for hours or delving deeply into a subject.

In my own incessant scrolling, I was fascinated to find an article in the Journal of Humanistic Mathematics (Vol. 12, issue 1, January 2022) by Firdous Ahmad Mala. He supports the argument made in 2009 by literature scholar Melanie Bayley that The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland carries a hidden meaning. Mala supports Bayley’s argument that Carroll (a mathematician, remember), didn’t appreciate how mathematics was changing in the Victorian era, and used nonsense verse in the Alice books to make his point. The article says:

“Mentions of magical mushrooms, babies transforming into pigs, and questions that have no answers were made to show how pointless, wasteful, and annoying these new [mathematical] theories were. A clothed white rabbit with a pocket watch, the hookah-smoking caterpillar, the mad tea party, and others seem to have been intended to ridicule the mathematicians and the theories they presented, which, to Carroll, were undermining the realistic touch and relevance that the old theories of algebra and geometry possessed.”

Lewis Carroll had an inquisitive and nimble mind. He loved playing games and inventing them. He created word ladders, (still given as homework to this day), as well as a device he called a nyctograph that let him record his thoughts without turning a light on. His nyctograph was a small card “containing a grid of cells that could guide his writing in the dark, using a peculiar alphabet he invented for the purpose.”

8. It’s a mystery story

Alice in Wonderland is a mystery, and I love mysteries! I suspect the answer to the question, “Who stole the tarts?” is in the same alternate universe as the answer to the riddle, “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” But no matter—there’s not really any evidence of a tart theft–it’s not even clear how many tarts there were. (I count ten in Tenniel’s drawing, but there may be more hiding underneath.)

9. It’s got an unforgettable tea party

You would expect the tarts to show up at the Mad Hatter’s Tea-Party, but that makes too much sense. Instead the Tea-Party offers up a most hilarious selection of nonsensical chatter, which Gardner’s The Annotated Alice assures us was likely inspired by Oxford philosophers Bertrand Russell, J. M. E. McTaggart, and G. E. Moore.

“The three men were known in the community as the Mad Tea Party of Trinity [College],” Gardner writes. McTaggart argued that time wasn’t real. Moore’s contribution to philosophy was, “a collection of arguments, puzzles and challenges.” And Russell’s work covered the philosophy of mathematics, metaphysics, ethics, and logic. I’m so tickled now to know that what reads like profound nonsense, which made me laugh out loud as a child, was Carroll’s take on this philosophical three-legged stool over beers at a local tavern.

And who is the dormouse falling asleep at the table? Gardner says it “may have been modeled after Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s pet wombat.”

That is a tea party I would give anything to attend.

10. It takes its nonsense seriously

In Alice and Through the Looking-Glass, Carroll mixes nonsense with math and science to entertain, to reference the works of others in his time, and to inspire. Gardner, in The Annotated Alice, writes that “most poems in the two Alice books are parodies of poems or popular songs that were well known to Carroll’s contemporary readers. With few exceptions the originals have now been forgotten, their titles kept alive only by the fact that Carroll chose to poke fun at them.”

Nonsense verse was popular in the mid-1800s, and both Carroll and Tenniel were known for it, part of the reason their work combined to such long-lasting effect, and it turns out that nonsense is far from just sheer silliness. In an article by Alison Gopnik, a professor of psychology and philosophy at University of California at Berkeley and an Alice fan,

“Children who play pretend and practice ‘believing the impossible’ tend to develop more advanced cognition. They are better at understanding hypothetical thinking, for instance, and they tend to develop a more advanced ‘theory of mind’, giving them a more astute understanding of other people’s motives and intentions.”

She also quotes Travis Proulx of Tilburg University in the Netherlands, who

“has found that by violating our expectations in a strange, alien world, fantastical stories pushes [sic] our brains to be more flexible, making us more creative, and quicker to learn new ideas. So if you are in a rut and feel like stretching your mind, you may find no better solution than an evening with Alice. ‘I have no doubt it stimulates these mental states that enhance learning and motivate us to make new connections.’”

A 157-year-old children’s book helping present-day scientists learn about what children need to succeed in the world as it is?!

“So many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.”

11. There’s a great (free) audio version

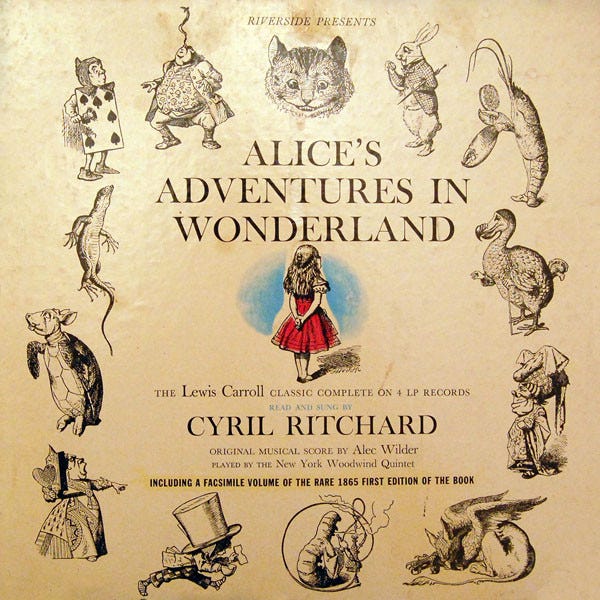

When my wish to hear my mother read Alice in Wonderland outstripped her available time (which happens to parents and educators and caregivers sometimes), she bought me the six-album set of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1957) and transferred it onto reel-to-reel tape.

At six years old, I could switch the roll from one side to the other and play it for myself as often as I liked. This unabridged version is narrated by the Australian stage actor Cyril Ritchard, with interstitial music by the American composer Alec Wilder, and it’s the only audio version for me.

Ritchard has a dramatic flair and dry delivery (he does the voices perfectly), and Wilder’s music is a sort of classical/jazz combo, sophisticated and quirky.

Pro tip if you’re reading aloud: Do the voices for the different characters, even if you don’t think you’re any good at it!

12. It’s a classic (but don't read it for that)

Philip Pullman, author of the His Dark Materials says,

“The sort of story we all hope we can write is one that will resonate like a musical note with all kinds of overtones and harmonics, some of which will be heard more clearly by this person’s ear, others by that one’s; and some of which may not be heard at all by the storyteller. What’s more, as the listeners grow older, some of the overtones will fade while others become more clearly audible.”

Perhaps this explains why children demand that we read the same story to them again and again. Reading Alice over and over recently, I remembered big thoughts and concerns like: Am I VERY small? Will I grow VERY large? How will I get where I need to go (the “the loveliest garden you ever saw”).

As Alice would say, it all gets “curiouser and curiouser.” It is up to us readers to stay with that curiosity children of all ages have, to dive into their questions and comments, to explore hand-in-hand new meanings or connections with children of all ages.

This book is a classic, but don’t read it because it’s a classic, read it because it’s a fantastical adventure story, because Alice is a superhero, because the language is still refreshingly crisp after over 150 years, and because the humor is bone dry.

You and your listeners will enjoy reading it over and over, a chapter at a time. Perhaps this dreamstory is more like real life than Carroll suspected. I think we’ve all gone down the rabbit hole and every day we’re living in Wonderland, doing our best to meet each day like Alice did: with curiosity, humor, grace, and courage.

Note: If you are reading aloud to a child who is very sensitive, maybe pre-read Chapter 6, “Pig and Pepper,” before you share it with a young listener. You may choose to skip parts of that chapter or take time to talk about how your family or group or school handles behavior like the Duchess’s.

Dana Gaskin Wenig is a writer, writing teacher, and former bookseller. She lives in the Seattle area.

320 Sycamore Studios is a children’s book publisher. Visit our Bookshelf page to read our stories for free. Books are also available for purchase on Amazon.

The mentioned mathematics paper in the article can be accessed from here: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol12/iss1/26/

13: When is a jar not a jar? When it’s Adore?

Why was the jar empty? Why was Dinah excluded from the Under Ground?