Reading with kids is an act of loving resistance against the uncontrolled growth of technology

I. We have a ChatGPT problem

In early May, a friend sent me a New York Magazine article titled, "Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College," by James D. Walsh.

Sheesh, I thought. Et tu higher learning? Everything really is going to hell.

I grabbed my handbasket and plunged into the article.

Walsh opens with a bang:

"Chungin 'Roy' Lee stepped onto Columbia University’s campus this past fall and, by his own admission, proceeded to use generative artificial intelligence to cheat on nearly every assignment."

From there, the article is just a cavalcade of bummers.

University students everywhere and all the time are using ChatGPT and other generative-AI chatbots to "take their notes during class, devise their study guides and practice tests, summarize novels and textbooks, and brainstorm, outline, and draft their essays." One survey cited in the article found that 90 percent of college students had used ChatGPT to help with homework assignments.

The upshot? Students aren't learning. And, as Cal State Chico ethics professor Troy Jollimore says, “Massive numbers of students are going to emerge from university ... who are essentially illiterate."

Since cheating is a technological problem, however, there's a technological solution: AI detectors.

Or maybe not.

Walsh writes that he "fed a chunk of text from the Book of Genesis into ZeroGPT and it came back as 93.33 percent AI-generated."

No worries, though, because there's always another technological solution. How about AI-generated essay feedback? Nope. The trouble, as Walsh points out, is “the possibility that AIs are now evaluating AI-generated papers, reducing the entire academic exercise to a conversation between two robots — or maybe even just one."

At the end of the article, Walsh returns to supercheater Lee, who by this point has been suspended from Columbia for going public with his cheating. No matter, because he's launched an AI startup called Cluely, which he hopes will further AI’s assault on education.

Its value proposition is, "You never have to think alone again." Compelling enough that the company has so far raised $5.3 million from investors.

I emailed my friend and thanked her for sending the article, thinking that would be the end of it.

My friend, however, replied with a question:

"Are we the last generation of thinkers?"

First of all, I’m uncomfortable with what “we” implies. I don't think I’m a thinker. I have friends who are literally philosophers, so I know what a thinker, um, thinks like. It's not me. I'm more of a plodding puzzler-outer. A riffer. A lexical muckabout.

I sent some useless reply, but her question nagged me.

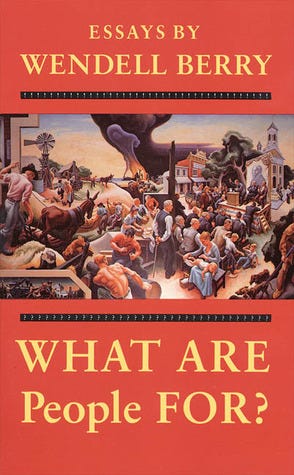

Truth be told, I was kind of hoping to skate through the rest of my life reading analog books and not caring about AI. I worked too many years for too many tech companies with too much "tech-data-productivity blah blah blah." I was so over it. I also knew that once I started thinking about AI, I'd have to think about questions like What is AI for and What is technology for and What is education for and What are people for?

And … How does any of this relate to reading with kids?

Part of me wanted to leave those questions to the pros. Let the philosophers and artists, the poets and monks give me the answers. Then I started thinking maybe that was the problem: my wanting to outsource my own thinking.

Besides, another part of me DID want to try and answer all these questions. I feel this compulsion to try and see. It’s like Doc Burton says in John Steinbeck's "In Dubious Battle": "I want to see the whole picture — as nearly as I can. I don’t want to put on the blinders of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, and limit my vision. If I used the term ‘good’ on a thing I’d lose my license to inspect it, because there might be bad in it. Don’t you see? I want to be able to look at the whole thing."

And then, if I could start to see it, maybe I could decide what to do about it.

So this is me trying to puzzle out an answer to the question “Are we the last generation of thinkers?”

To answer it, I think a person needs three things:

a framework for thinking about technology

a vision of what human life is for, and

a plan for how to live it.

Oy, the hubris. Forgive me.

II. We have a technopoly problem

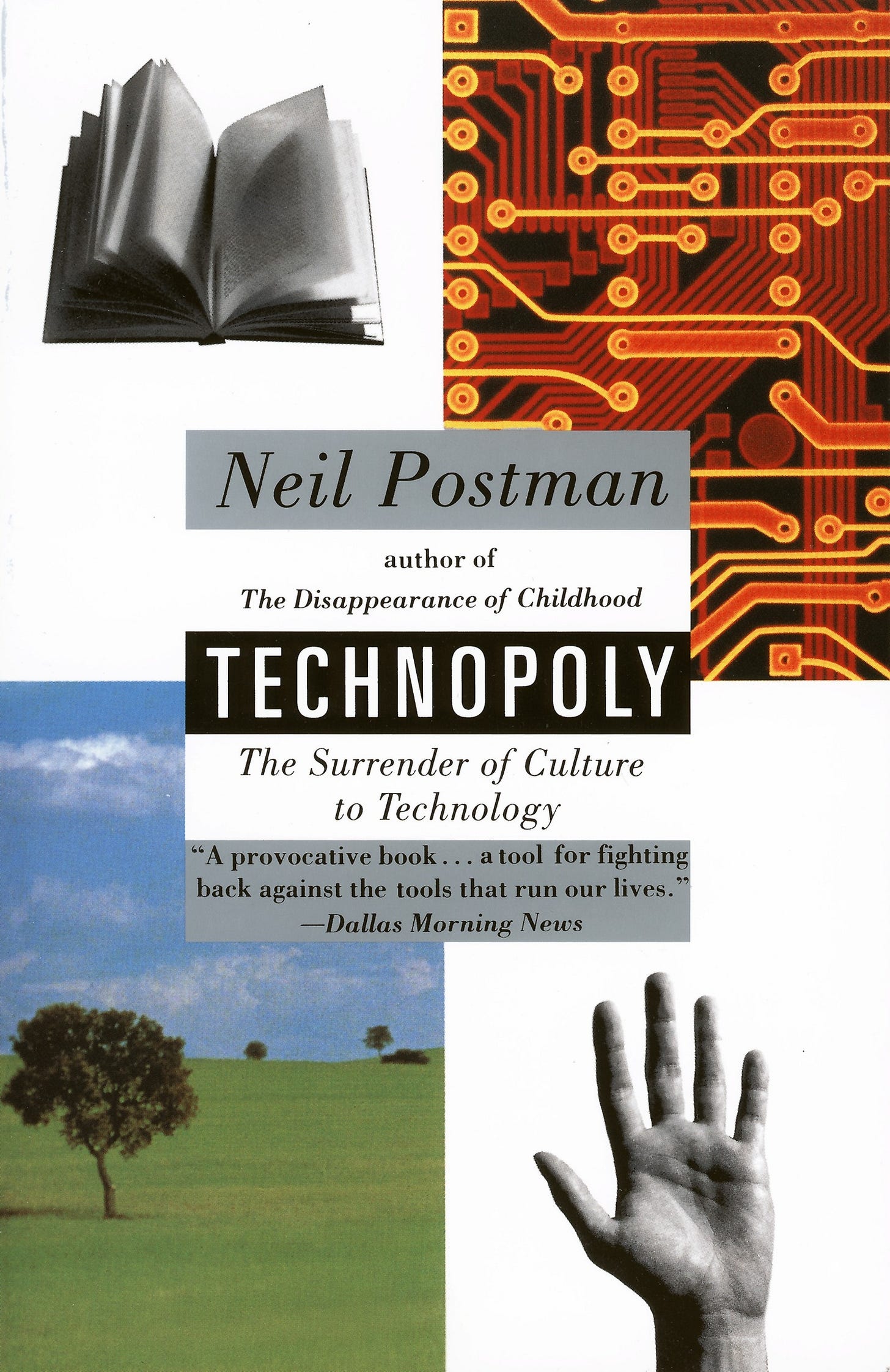

To sharpen up my thinking, I reread Neil Postman's timeless 1993 book "Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology."

Postman was a media theorist, social critic, writer, chairman of NYU's department of culture and communication, and the author of 20 books, including "The Disappearance of Childhood," "The End of Education," "Amusing Ourselves to Death," and "Conscientious Objections." (All great, by the way.)

In "Technopoly," he argues that "The uncontrolled growth of technology destroys the vital sources of our humanity. It creates a culture without a moral foundation. It undermines certain mental processes and social relations that make human life worth living."

Yikes.

Postman doesn't argue against technology per se. Technology is not "good" or "bad." A book is a technology. A pencil is a technology. Rather, his argument is about what vision technology serves. A human (and humane) vision? Or something else?

It’s feeling like “something else” these days, and that something else is called “technopoly.”

Technopoly, he writes, is "the submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology." He contrasts that with two broad earlier phases of human development, which he calls "tool-using" and "technocratic." Tool-using cultures are those where tools are subordinate to belief systems or wisdom traditions. Technocratic societies are those in a transitional phase, where older belief systems are under attack. (Think Galileo and the Catholic church).

You can never say when one thing becomes another, but Postman finds 1911 a useful date for the origin of technopoly. That was the publication year for Frederick Taylor's "The Principles of Scientific Management," which

"contains the first explicit and formal outline of the assumptions of the thought-world of Technopoly. These include the beliefs that the primary if not the only, goal of human labor and thought is efficiency; that technical calculation is in all respects superior to human judgment; that in fact human judgment cannot be trusted, because it is plagued by laxity, ambiguity, and unnecessary complexity; that subjectivity is an obstacle to clear thinking; that what cannot be measured either does not exist or is of no value; and that the affairs of citizens are best guided and conducted by experts."

If you're like me, it takes a lot of work to argue against these ideas. (What, we’re supposed to be less efficient? Can human judgment really be trusted?) Especially if, like me, you’ve spent a career working in organizations that fetishize quantification. All that datacentricity (what a horrible word, sorry) gets into your blood. Alternate ways of thinking can be hard to come by.

Which is Postman's point:

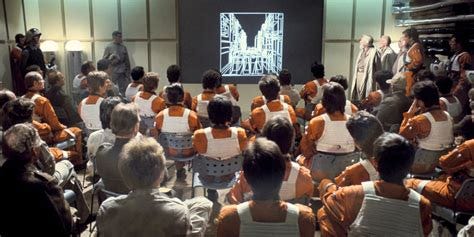

"Technopoly eliminates alternatives to itself in precisely the way Aldous Huxley outlines in "Brave New World." It does not make them illegal. It does not make them immoral. It does not even make them unpopular. It makes them invisible and therefore irrelevant."

Here's an example. Think of how weird it would be to not receive letter grades for schoolwork. Yet Postman writes that this is a peculiar idea.

"What is even more peculiar is that so many of us do not find the idea peculiar. To say that someone should be doing better work because he has an IQ of 134, or that someone is a 7.2 on a sensitivity scale, or that this man's essay on the rise of capitalism is an A minus and that man's is a C plus would have sounded like gibberish to Galileo or Shakespeare or Thomas Jefferson. If it makes sense to us, that is because our minds have been conditioned by the technology of numbers so that we see the world differently than they did. Our understanding of what is real is different. Which is another way of saying that embedded in every tool is an ideological bias, a predisposition to construct the world as one thing rather than another, to value one thing over another, to amplify one sense or skill or attitude more loudly than another."

That's what Marshall McLuhan meant when he wrote that the medium is the message.

Postman relates a story from Plato of the Egyptian king Thamus who cautioned against the unquestioning embrace of technology. Technology creates winners and losers, and the losers are losers in part:

"because they believe, as Thamus prophesied, that the specialized knowledge of the masters of a new technology is a form of wisdom. The masters come to believe this as well, as Thamus also prophesied. The result is that certain questions do not arise. For example, to whom will the technology give greater power and freedom? And whose power and freedom will be reduced by it?"

It's evident who technopoly’s "winners" are. They’re the ones running the world just now. (By the way, for a thoughtful look into the new economics of technology, power, and capital, check out "Technofeudalism" by Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis).

The rest of us losers don’t have a ton of options. But if "certain questions do not arise" in us, we run the risk that we'll stop thinking for ourselves. Of letting technology’s true believers — or their creations — think for us.

3. Reading with kids as an act of loving resistance

So what are the options?

Postman’s suggestion is this: "You must try to become a loving resistance fighter."

Cool!

Who doesn't want to join the Rebel Alliance and fight the Galactic Empire? (Sorry, I just finished watching "Andor" recently and I have "Star Wars" on the brain.)

But, um, what does "resisting" mean, exactly?

To Postman it means understanding that "every technology — from an IQ test to an automobile to a television set to a computer — is a product of a particular economic and political context and carries with it a program, an agenda, and a philosophy that may or may not be life-enhancing."

Okay, what are we fighting for? (What's the vision?)

And how are we supposed to fight? (What's the plan?)

The vision

Postman suggests this: "the ascent of humanity."

It's an idea he borrows from the work of Polish mathematician-philosopher Jacob Bronowski. "The ascent of humanity" is a grand human narrative where science, art, the humanities, and religion all play their part in telling the story of "humanity's creativeness in trying to conquer loneliness, ignorance, and disorder."

Nice. But maybe that sounds a bit ... airy.

If it does, consider that vision is at the heart of the military theory that reshaped the U.S. Marine Corps in the 1980s:

"What is needed is a vision rooted in human nature so noble, so attractive that it not only attracts the uncommitted and magnifies the spirit and strength of its adherents, but also undermines the dedication and determination of any competitors or adversaries."

— Source: "Patterns of Conflict," Col. John Boyd

Or consider that a vision is also the cornerstone of corporate brand-building. When I worked as a marketing copywriter, I used to create these documents called "brand messaging frameworks." That's a fancy term (I mean, it was marketing, after all), but the docs were basically just structured descriptions of a company's product, audience, key differentiator, vision, mission, values, etc. Anyway, one of the key questions I'd always ask was, "Why do you exist?" If a company could articulate their vision — the impact they wanted to have on the world — it was then a straightforward process to create their brand, strategy, marketing, culture, and so on.

Or consider the moonshot that got a man to the moon.

Vision matters.

If humans turn the “why do we exist?” question back on ourselves, we could do a lot worse than answer it with “to participate in the ascent of humanity.” Humanity as human knowledge, as creative expression, and maybe most importantly, as empathy.

For my part, I've found that even in my bleakest times, I've been pulled forward by a desire to learn and create, as well as a desire to expand my own humanity. If I make life decisions with a mind to curiosity and empathy, I know I’m on the right track.

The plan

As for the "what do we do to become a loving resistance fighter" bit, I think the answer has at least two essential parts.

Get together with other people and make "good trouble."

Read to your kids a little every day until they're 18 to help them become their best selves (and maybe save the world).

Regarding point No. 1, see the work of the late, great Rep. John Lewis. Or this guy, still fighting the good fight. Or any group of folks getting together to make things better.

Regarding point No. 2. I not so coincidentally wrote a paper with that exact title. You can read it here, but the point is that reading with kids is immensely powerful.

How powerful?

Reading aloud helps kids grow their brains. It develops academic skills, like: active listening, comprehension, critical thinking, fluency, inflection, syntactic development, pronunciation, vocabulary acquisition, and writing.

Reading aloud helps kids grow their humanity. It develops personal skills like: attention, curiosity, cultural sensitivity, emotional intelligence, empathy, self-discipline, imagination, and self-esteem.

Reading aloud deepens bonds. In the family and in the classroom.

Reading aloud helps kids learn to love reading. And that makes them more likely to do it themselves. That's how it was for me. I was read to when I was small, and later, books became a refuge and a window. A refuge because when I read, I couldn’t hear the voices telling me I wasn’t good enough. A window because to read is to see other ways of being. I read and I learned I wasn’t alone.

Our motto at 320 Sycamore Studios is “Reading with kids can change the world for the better.

I think that’s because reading with kids gives. Technopoly takes.

Indeed, reading with kids is the opposite of technopoly.

It feeds the vital sources of our humanity.

It nourishes a culture's moral foundation.

It fortifies the mental processes and social relations that make human life worth living.

And to think — all you need is a library card.

Will we be the last generation of thinkers?

Not if we keep reading with our kids.

It really can change the world for the better.

— Jeff

PS. As great as books are, they, too, are a technology. So keep in mind what preschool teacher Karissa Pelletier told me once:

"With our circle time read-aloud, we just play it by ear. Some days it could be 20 minutes, some days it could be four minutes. There are definitely days where we don’t get through a book, where we have to put it down and just dance."

Some days you just have to dance.

I always smile when I read your emails. You have such a fresh and loving way to get your point across. Thank you for all you do!

Thanks for the insight. When all around us is noise about money, politics, and human suffering, it is good to know that the simple act of sharing a book with my granddaughter is good work.