A book for 'those who still keep the spirit of youth alive in them'

Dana Gaskin Wenig on 'The Wind in the Willows,' our Sustaining Book for June

Each month, writer and children’s book expert Dana Gaskin Wenig chooses an enduring children’s book or new classic to explore in depth. This month, she dives into the timeless enchantment of “The Wind in the Willows,” from Kenneth Grahame.

The Wind in the Willows: Always something new to discover

There are a handful of books that feel like part of my body.

These are books that my parents read to me before I knew how to read to myself, before I differentiated myself from the characters in the story. I consumed these stories as truth and assigned my family members the roles in the books. This stack of books includes Winnie the Pooh, by A. A. Milne, The Owl and the Pussycat, by Edward Lear, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll, The Bear that Wasn’t, by Frank Tashlin; Just So Stories, by Rudyard Kipling; and The Wind in the Willows, by Kenneth Grahame.

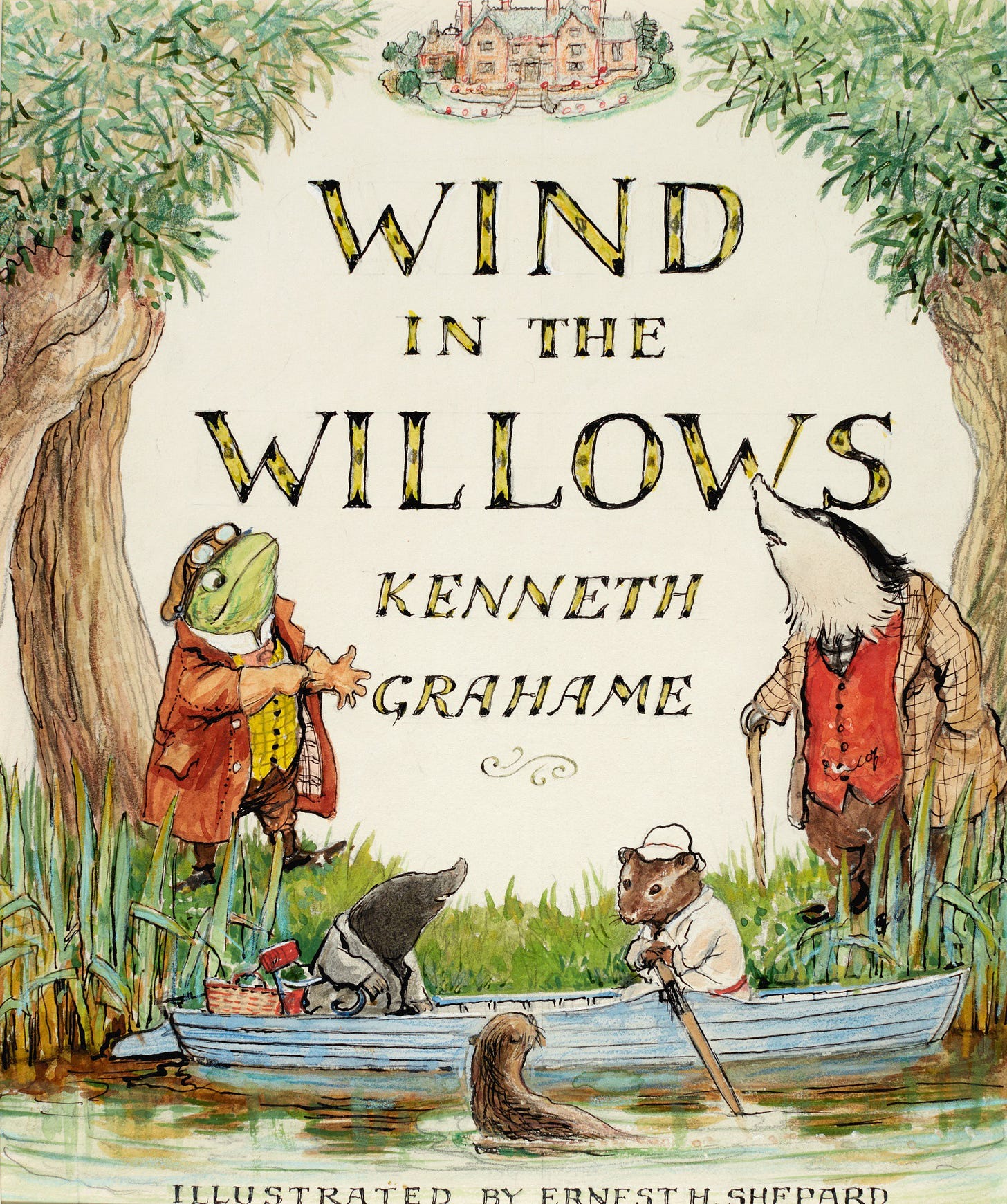

I’ve read The Wind in the Willows (and had it read to me) more times than I can count: my mother read it to me, I read it to myself, and I read it aloud to my grown daughter when she was small. In preparation for this article, I listened to the book, but wanted to read it as well. Sadly, the only physical copy I could find in my house was a large-format edition with illustrations by Michael Hague, an American illustrator. If you’re stuck on a desert island with that edition, please do read it, but know that you are missing the first (read “real”) illustrations by Ernest H. Shepard, also known for his original illustrations of Winnie-the-Pooh.

So, this former bookseller took herself to her local (independent) bookstore and bought a new hardcover of The Centennial Anniversary Edition with the original illustrations and a preface written by Margaret Hodges, Professor Emeritus, School of Library and Information Science, University of Pittsburgh.

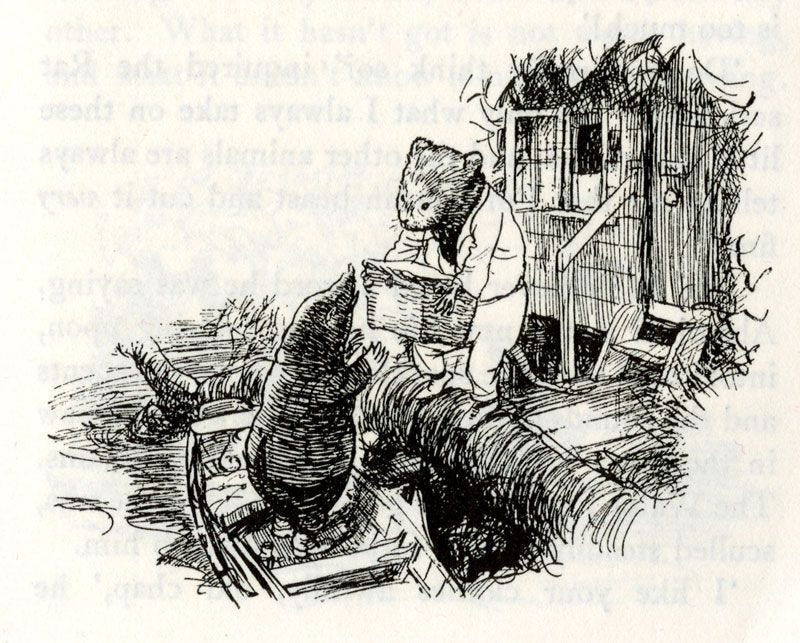

The preface is well worth reading, as Hodges offers background information on Grahame, and Shepard, and the roots of this classic. This matter of the illustrations may seem petty, but I encourage you to hold out for the originals. Shepard’s line-drawings are dear, and finely drawn, and the color illustrations light up the page. There is a short note at the end of this edition in which Ernest H. Shepard invites us into the room when he and Kenneth Grahame meet. Grahame tells him, “I love these little people, be kind to them,” and sends him off for a walk along the riverbank. The next time Shepard visits to show Grahame his sketches, Grahame responds, “I’m glad you’ve made them real.”

There is a short list of classic children’s books that came into being because a child demanded that an adult, often a parent, “Tell me a story!” (Just So Stories, Alice in Wonderland, and The Tale of Peter Rabbit, by Beatrix Potter, come to mind.)

No giraffes, sadly

In this case Grahame’s son Alistair struggled, like so many of us do, with the transition to sleep. More than a hundred years before the podcast and the Kindle, Grahame sat beside his son’s bed and let Alistair chose the characters (although the book doesn’t reflect his request for giraffes), while he created adventures rooted near the Thames, where they lived, and peopled by the animals they observed there. What comes through in each chapter is a spacious and season-driven love of the natural world, the generosity of devoted friendship and community, the importance of home, and a sense of nostalgia that is unshakeable.

Only nine children’s books were published in England in 1908, and of those nine you will likely find only four in a bookstore today: Anne of Green Gables, by Lucy Maud Montgomery; Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz (the fourth in the Oz series), by L. Frank Baum; The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, by Beatrix Potter; and The Wind in the Willows.

Kenneth Grahame described The Wind in the Reeds (the original title) to Charles Scribner’s Sons publishing house as:

A book of youth, and so perhaps chiefly for youth and those who still keep the spirit of youth alive in them; of life, sunshine, running water, woodlands, dusty roads, winter firesides…

Initially published without illustrations, the book was released to mixed reviews, but soon gained fans. One of them was President Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote to the publisher, saying “he thought of the characters as old friends.”

By now, The Wind in the Willows has sold nearly 30 million copies in multiple languages.

‘Divine discontent and longing’

Chapter One finds the Mole whitewashing the walls of his den. Suddenly he feels Spring “moving through the air above and in the earth below and around him, penetrating even his dark and lowly little house with its spirit of divine discontent and longing.” He drops his tools, sheds spring-cleaning, and set out on his adventure. The Mole “rambled busily” through the countryside until:

Suddenly he stood by the edge of a full-fed river. Never in his life had he seen a river before — this sleek, sinuous, full-bodied animal, chasing and chuckling, gripping things with a gurgle and leaving them with a laugh, to fling itself on fresh playmates that shook themselves free, and were caught and held again. All was a-shake and a-shiver — glints and gleams and sparkles, rustle and swirl, chatter and bubble. The Mole was bewitched, enchanted, fascinated.

You have a sense now of Grahame’s gift for language. This could just as well be lines from the poem Pied Beauty by Gerard Manley Hopkins. He continues with the Mole:

By the side of the river, he trotted as one trots, when very small, by the side of a man who holds one spellbound by exciting stories; and when tired at last, he sat on the bank, while the river still chattered on to him, a babbling procession of the best stories in the world, sent from the heart of the earth to be told at last to the insatiable sea.

It is in this state of joy and discovery that the Mole encounters the Water Rat. This friendship, and Mole’s gradual entry into the world of the river and the community that surrounds it, is never moralistic, but shows a deep regard for, and knowledge of, the natural world, of healthy friendship, and of the importance of home.

Ratty is that generous friend who laughs kindly when we make a mistake and then helps us clean it up without causing further shame. He is the friend who notices you’re not home at the usual time and comes looking for you in the Wild Wood. He’s a true friend.

Two separate books put into one

In his memoir The Enchanted Places, Christopher Robin Milne, A. A. Milne’s only son, wrote this about The Wind in the Willows:

This book is, in a way, two separate books put into one. There are, on the one hand, those chapters concerned with the adventures of Toad; and on the other hand there are those chapters that explore human emotions — the emotions of fear, nostalgia, awe, wanderlust. My mother was drawn to the second group, of which "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" was her favourite, read to me again and again with always, towards the end, the catch in the voice and the long pause to find her handkerchief and blow her nose. My father, on his side, was so captivated by the first group that he turned these chapters into the children's play, Toad of Toad Hall. In this play one emotion only is allowed to creep in: nostalgia.

It occurs to me that encouraging parents and caregivers and educators to read aloud to children may not be enough at times, perhaps it’s helpful to look at why we don’t feel moved to read to children.

Isn’t boredom one element of why we are sometimes reluctant to read to kids? The material doesn’t touch us, or we’ve read a book aloud to a child so many times that it has no more surprises? The Wind in The Willows is never over, in a sense. There is always some new detail to discover, an illustration to be pored over and discussed, a review of the intervention into Toad’s troubles, or a planning session for a boat trip. Some chapters that will need to be read over and over, some skipped at first depending on temperament or age.

An unstoppable river of pop-culture inspiration

As Milne says, it feels like two books, one about the idyllic friendship between the Mole and the Water Rat, and a second about the wild and lovable Toad and his suspenseful adventures. And the tales really don’t end. At least eight sequels were published between 1981 and 2020 (some only in audible book form), some of them shifting the lens of the story to address class differences, some gender.

My favorite of these is Kij Johnson’s 2017 book The River Bank in which she introduces female characters (finally) to the tale. Using language equally as lyrical as in the original, with gorgeous illustrations by Kathleen Jennings that are modern, but pay homage to Shepard’s illustrations, it belongs on the shelf beside this edition.

The Wind in The Willows runs through popular culture like the river at the center of the story. What do Downton Abbey, Stevie Wonder’s song Flower Power, The Simpsons, the movie Wicker Man, Rugrats, Disneyland, and Iron Maiden have in common? The Wind in the Willows.

The book also inspired Debbie Harry, Van Morrison, Tower of Power, and Dutch composer Johan de Meij. Fans of English rock-and-roll will recognize the title of Pink Floyd’s debut album, Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967) when they get to Chapter Seven. This golden chapter falls in the center of the book, and it is perfect.

The Water Rat returns home from a visit with Otter whose son Portly, who hasn’t yet learned to swim, has been missing for days. This is the story of a father’s love for his son and so much more. Of course, Mole and the Water Rat decide they must help, and they take to the river to look for the young otter. You’ll get no spoilers here.

Into the ‘back-kitchen of the unconscious’

My hope is that you have had the good luck to love a river (or many rivers) like I have. I hope you’ve had access to clean, clear streams or creeks or rivers in which to raft, swim, fish, and boat, and that these memories bring nostalgia to your heart. I hope you still experience rivers, and that you find time to sit beside them to hear their rippling stories. If you have, this book will bring beautiful memories, and if not, let this book allow you and your listener to share in that experience. It’s easy to think a children’s book that is more than a hundred years old is past the point of sharing modern concerns, but Kenneth Grahame was aware of the press of civilization on the forests and waterways he loved; this book is a love letter to nature and her creatures for the ages.

Read this book aloud to children as early as they are patient enough for a book without an illustration on every page, to students, friends, young adults, significant others, and your parents if they will allow it, because it’s magic. We humans/animals are rooted in earth, in water, in friendship and community care, in each other. Books like this leave teaching moments behind, because the act of reading them aloud to someone, in combination with the stories themselves, is the moment, is the message: we are here together, we are earthen creatures, all of us, water is life, caring for one another and our environment is our natural state.

Grahame once told his friend Constance Smedley, “I feel I should never be surprised to meet myself as I was when I was a little chap of five, suddenly coming round a corner . . . The queer thing is, I can remember everything I felt then, the part of my brain I used from four till about seven can never have been altered.”

This explains the accessibility of these stories, they are, in a sense, written by his child brain, for children of all ages. In the preface to this edition, Hodges remarks that Grahame “has taken us with him down into what he once called ‘the back-kitchen’ of the unconscious, where the dream kettle boils the brew of what we really care about.”

What a relief to finally have an explanation for why this book feels like part of me.

Dana Gaskin Wenig is a writer, writing teacher, and former bookseller. She lives in the Seattle area.